WHY DO WE LOVE AUTOMATIC MECHANICAL WATCHES?

Everything you need to know about one of man's most important innovations

We tend to love complicated things that work amazingly well – even if we have no idea how. In this article, we’ll lift the veil on how mechanical watches work to let your spark of curiosity blossom into a deep appreciation.

Mechanical watches, especially skeleton watches,are true works of artistry. Their tiny gears, springs, and gorgeous jewel bearings hypnotize you as they transfer power from one element to another in a dance of forces so finely tuned as to accurately measure the passage of time.

HOW WE MADE MECHANICAL WATCHES

The first watch was a sundial. As time-keeping devices go, they’re pretty accurate. Too bad they only work half the time and only when the weather allows. Through the ages, we’ve come up with many ways to measure and tell time, from water clocks to hourglasses to candle clocks and beyond. Asian cultures even had incense clocks that allowed people to tell time by the fragrances released from expertly crafted incense holders.

Early clocks were wildly inaccurate. Springs drove the hands around the dial, but their speed varied depending on the tension of the spring. They’d go way too fast in the morning and slow down as the day went on. Many of us wish that were still the case.

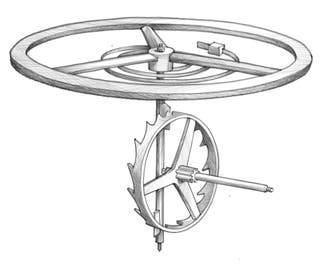

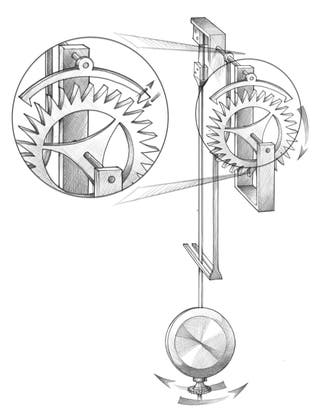

In 1656, Dutch inventor Christiaan Huygens made clocks 60 times more accurate with the invention of the pendulum clock. The revolutionary thing about it was that it introduced the first harmonic oscillator for accuracy. The power source of these clocks was a weight that pulled on the gears and drove the pendulum back and forth. The pendulum was connected to the pallet fork, so each swing let the gears move a specific amount. Since the force of gravity is constant, the force pulling on the weight and the pendulum keeps the clock running consistently. The same principle is at work in the opposing pushes of the mainspring and the hairspring acting upon the balance wheel in modern mechanical watches.

TYPES OF MECHANICAL WATCHES

Mechanical watches come in three varieties – mechanical, automatic, and automatic mechanical. All three have a mainspring as a power source that needs to be wound, and the difference lies in how you wind them.

MECHANICAL WATCHES

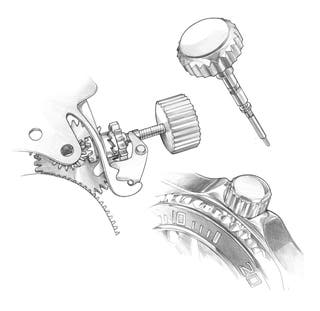

A mechanical watch can only be wound using the crown. This is the most common type of movement in pocket watches and vintage mechanical timepieces. Rotating the crown turns the mainspring tighter, adding to the watch’s power reserve.

AUTOMATIC WATCHES

Purely automatic watches are rare, but they do exist. These cannot be wound by rotating the crown but only by applying movement to the watch itself. Behind the caseback is a half-moon-shaped oscillating weight. This rotor weight winds the watch as you move your arm, swinging internally as you swing your arm. The idea is that if you wear the automatic watch every day, it builds up enough power to last through the night, so it shouldn’t ever stop. Put it on the next morning and head to work, and you’ll generate enough power to run the watch continuously and top it up for the next night. If it does stop, however, you may have to shake it a bit before it gets going. Don’t be too rough, though. The springs and gears really don’t like that.

AUTOMATIC MECHANICAL WATCHES

Most modern mechanical watches feature automatic mechanical movement. They can be wound with the crown and keep themselves topped off with the movement of your hand. If you find your automatic mechanical watch stopped, turn the crown a few times until you see the second hand start racing. Then it’s safe to put the watch on as the rotor weight will do the rest.

HOW MECHANICAL WATCHES WORK

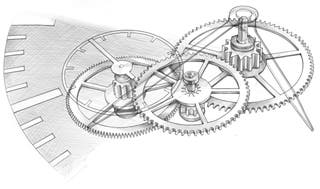

Whichever way your mechanical watch adds power to the mainspring, this is where the dance starts. If you were to take the mainspring out of the barrel that contains it, it’d quickly uncoil into a 20-30 cm long steel band. This is the state it’s constantly trying to get back to, and that is the force that drives the watch.

From the mainspring, power runs through the wheel train. These are the gears that drive the hands around the dial and run the various complications your watch may have, such as the chronometer, date window, moon phase window, etc. How many gears your watch has depends on its number of complications.

The motion works perform a 12/1 speed reduction on the movement of the minute hand for the hour hand. When you pull the crown out to set the time, the crown connects directly to the motion works to allow them to rotate freely as you turn the crown. When you push the crown in, the motion works are reconnected to the wheel train, and the watch starts running again.

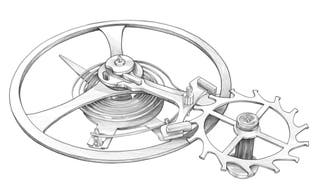

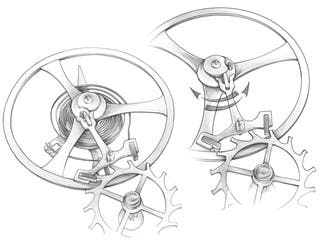

The ticking heart of your watch – and arguably its most vital features – are the escapement and balance wheel. As power flows into the balance wheel, it swings back and forth at a steady rhythm. This rhythm is maintained by the hairspring, which pushes back against the force coming from the mainspring. Without this counter-push, the hands on your watch would just spin around the dial at dizzying speeds as the mainspring unwound itself fully in one go. The weight of the balance wheel gives it momentum, causing it to push against the hairspring. The hairspring is stronger than the mainspring and pushes the balance wheel back. The more power you’ve stored in your mainspring, the further and faster the balance wheel turns. Less power means slower and shorter movement.

The pallet fork is moved by the balance wheel. A jewel pin on the balance wheel bumps into the pallet fork, knocking it sideways and releasing the escapement from one side and grabbing it with the other. When the balance wheel comes back around, it knocks it back, releasing the escapement again. These increments are the finely-tuned movement of the watch, and the sound of the pallet fork jewels grabbing the escapement is the ticking of your watch. The hairspring has regulator pins, allowing watchmakers to adjust its tension in case your watch is running too fast or too slow. An expertly tuned mechanical watch is accurate to about 2-3 seconds per day.

Skeleton watches allow you to see this dance happening as your watch runs but are sometimes considered more difficult to read as the hands get lost in the visual complexity of the movement below them. Luckily, we have multiple designs that address this problem, such as our Fenes and Cor collections. For the full view, our Dante or Mamut collections are superb options.

WHAT TYPE OF MECHANICAL MEN’S WATCH SHOULD I WEAR?

For the type of guy who wears waistcoats, a mechanical pocket watchis the ultimate touch. If you’re an insatiably curious soul who just has to know how things work, a skeleton watch puts that part of you on display. For those who appreciate classic, clean design, automatic mechanical watches with minimal complications will serve you well and last longer. The variety of mechanical watches on the market is virtually endless. You’re bound to find one that matches your character and sense of aesthetics.

YOU ASKED – WE ANSWERED

The bearings on your watch are usually made of synthetic sapphire or ruby. These provide an almost frictionless seating for the gears to rotate, so minimal loss occurs during the transfer of power between components. This increases both the longevity of your watch and its accuracy.

Not necessarily. As long as every bearing has a jewel, and the pallet fork and balance wheel impulse pin are made of synthetic ruby or sapphire, you’re good. More jewels usually means more complications, which is fine if that’s what you’re after, but it shouldn’t be your primary motivation for picking one watch over another.

Definitely. Check out our watches category where you can filter by movement.

That depends on what you mean by “better.” Quartz watches are more accurate than mechanical watches, but you have to change batteries regularly. And if it’s out of batteries, it’s pretty much useless until you get it to a watchmaker. Mechanical watches run on good old-fashioned kinetic power. If it’s stopped, simply wind it up and set the time. Both have pros and cons.

Yes. Mechanical watches are more expensive than Quartz, sure, and if you just want a watch that tells time, feel free to get one of those. But if you want to wear a part of history around your wrist – a testament to human ingenuity that has been continuously improved since 1275 CE, go for a mechanical watch.

A pocket watch that runs on a wound mainspring rather than battery-powered Quartz movement. Some pocket watches even feature automatic manual movement, transferring the energy of your gait to the mainspring, keeping it wound.

A mechanical watch is any watch that uses kinetic force stored in a mainspring as a power source, releasing that power through a series of gears to drive hands around a dial to display time.

That depends on how you wind it. Using the crown, you can overwind the mainspring and deform it. Worst-case scenario, this forces it out of its barrel, rendering your watch useless. Only use the crown to get the watch started if it's stopped, and then rely on your movement to keep it topped up.

The rotor connected to the ballast weight that winds the mainspring using your movement has a clutch that automatically disconnects it from the mainspring when fully wound. This prevents overwinding as you go about your day.

If you have to use the crown to wind your watch, stop as soon as you feel the slightest increase in resistance. This means the spring is starting to feel uncomfortable in its barrel, and you need to let it unwind.

No. If you wear an automatic watch every day, you’ll never have to worry about winding it. It’ll keep itself wound using the motion of your wrist.

Not as much as you might think. They’re still more expensive than Quartz watches, but thanks to mass-production companies that specialize in machining high-quality, high-precision components and movements, the cost of reliable automatic mechanical watches has come down quite significantly in the past few years.

What’s so good about classical architecture? What’s so special about vintage sports cars? A mechanical watch is a piece of history strapped to your wrist. We’ve been continually improving upon the mechanics of timekeeping and watchmaking for almost 1000 years, culminating in the modern automatic mechanical men’s skeleton watch. Battery-free, self-winding movement with the hypnotic dance of the gears and springs inside on display. It’s like wearing Leonardo da Vinci.